|

| Character art for Rydia of Mist for Final Fantasy IV: The After Years. Art by Yoshitaka Amano; ©2008 Square Enix |

Final Fantasy: A Brief History

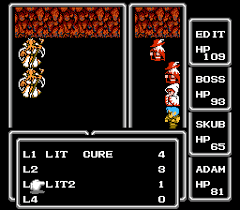

If you aren't familiar, the early Final Fantasy games were designed to imitate OD&D with a dash of Expert and Companion mechanically. The cleric was rebranded as a white mage, the magic user a black mage (and spells mostly simplified to attacks), the monk was renamed "black belt." A sword wielding spellcaster with limited access to both healing and attack magic was created called the Red mage, Fighters and Thieves remained Fighters and Thieves; the latter has the ability to steal extra treasure and potions from enemies. In the first two games, you built a party of four and went on an adventure to save the world

|

| Mind Flayer attack in Final Fantasy the Flayers were renamed "Wizards" |

While many of the Final Fantasy games were breakaway hits globally, the first few English translations: Final Fantasy, Final Fantasy IV (sold as "Final Fantasy II" originally), Final Fantasy VI (sold as "Final Fantasy III"), Final Fantasy Seiken Densetsu ("Final Fantasy: Mystic Quest") and Final Fantasy Seiken Densetsu 2 (sold as Secret of Mana) were relatively niche products that sold primarily to Dungeons & Dragons players.

It wasn't until the release of the more cyberpunk Final Fantasy VII on the PlayStation that the games found more widespread popularity with video gamers who weren't also fans of D&D.

These early games were simplistic adventures with a linear series of dungeons to explore and combat as the only real means of solving problems.

As the series evolved, the mechanics drifted somewhat from D&D, and it made up for the lack of non-combat solutions to problems by making combat increasingly complex. To make up for the necessary railroading that games required at the time, the characters were given dialogue, unique identities with backstories, motivations and complex relationships to add a sense of complexity to the game's plot.

By Final Fantasy IV hit the Western market these stories had become fairly compelling, if a bit soap-operatic. A large cast of playable characters came and went from the party, often sacrificing themselves heroically for the cause only to return in dramatic battles. Plot twists and revelations were your reward for exploring the dungeons and defeating the enemy

Thanks to the overlap in fandoms, Final Fantasy IV's plot and characters, were beloved by many Dungeons & Dragons players who also played Nintendo games. Especially ones who had started the game relatively young in the mid-80s (Mentzer Box kids like me.) In fact, several outlets have stated that Final Fantasy IV raised the bar for storytelling in both video games and the fantasy genre in general. It is being a visible influence on the genre of high and heroic fantasy for decades now.

With the already burgeoning focus on campaigns with an overarching narrative that had come from the Dragonlance modules and novels, and early Forgotten Realms material like Under Ilefârn, Final Fantasy IV provided GMs looking for a model of plot structure to emulate.

The Mark of the Early Games

On the upside, Final Fantasy IV posted a huge cast of characters both player characters and NPCs that range from the helpful to the fiendish. It embraced stories of valor, heroism, self-sacrifice and courage which made it stand out in the video game world. The characters also weren't sacred. One ended up dead, and another permanently crippled early in the story. Another spent over half the campaign enslaved under mind control that was bolstered by his jealousy of the hero.

The world itself was sprawling, and had more that players had to discover in order to move forward. These are all characteristics I consider fantastic if you want to campaign that is long-lasting and satisfying to your players.

Final Fantasy VI, while less influential in retrospect, was not afraid to mix science fiction and fantasy in ways that felt a lot like the work of Jack Vance, and helped push players of the age away from focusing on the Tolkeinian fantasy that Forgotten Realms and Dragonlance had made the default for D&D. The story of FFVI includes a madman stealing the powers of the gods and bringing about an apocalypse that the PCs survive, scattered. The latter half of the game is about survival and rebuilding. The "world shaking event" plot pivot become a core of how campaigning Dungeons & Dragons is taught and played.

The villains of FFVI were complex, and in some cases were decent, noble people with good intentions serving a bad cause. They strongly encouraged creating villains with depth and complexity. And where there were villains so vile as to be irredeemable, they gave reasons for how the character became monstrous that makes them at least a little sympathetic.

Other elements, such as a little whimsy, a conscious choice to create a fantastical world rather than an attempt to simulate Medieval Europe, and the import of a number of Japanese storytelling and character tropes all had a positive impact on how Fantasy RPGs were played.

|

| Final Fantasy IV cast portrait; Art by Yoshitaka Amano; ©1991 Squaresoft |

The Bad

On the other hand, Final Fantasy games can be ham-fisted in service to it s narrative. Plot takes precedence over player agency, even at the expense of ruining the players' sense of accomplishment.

In every early Final Fantasy there were battles you were not meant to win or that you could only win if you made choices preferred by the developers. More than once, a terrible monster shows up and scatters the party to where they need to be for the next step of the plot, with no recourse by the players.

The primary villain of FFIV, Golbez doesn't follow the rules, he survives supposedly un-survivable attacks that cost player characters their lives, stealing your victory out from under you several times, making heroic sacrifices hollow.

|

| Hello, Nurse! |

Most significantly, the narratives of Final Fantasy require a hero with a mysterious past to function. While all other characters come and go, the character of Cecil is always front and center to the story. He serves as its chosen One, moral compass, and his knowledge serves as the constraint on the players point of view.

Final Fantasy VI added in the aggravating archetype of the silent edgy loner helps who the party and then leaves it or betrays it, the tragic swordsman who was motivated only by avenging his lost family, royal twins who parted ways for one to become a wandering hero, and magical mimes who can initiate any skill they see.

None of these on their own are particularly heinous and work fine for what is essentially of fantasy novel delivered by menu-based strategy game

Lost in Translation

However, attempting to shoehorn them into role playing games... That is very tricky ground.

It doesn't take you long reading through something like r/rpghorrorstories to come across someone attempting to shoehorn tropes from or popularized by the Final Fantasy games:

- GMs giving a character the role of chosen hero.

- Suddenly changing a villain on the fly to nullify a PCs success.

- Battles PCs are "meant" to lose.

- Mind-controlled allies turning on the players

- Edgelord loner PCs (especially ninjas or guys with vicious dogs.).

- Heroes who discover that they magical inhuman bloodlines. (FFVI and FFVII)

- PCs who refuse to speak (FFVI)

- Characters that wield impossible swords (FFVII)

- Secretly gender-bent PCs (FFV)

- Witholding a PC's knowledge via amnesia until a critical moment has passed (FFV)

These tropes foisted on a game of D&D are great ways to kill a campaign

|

| Edgelord Patient Zero If you have suffered through a dark, mysterious PC who never talks and goes off on his own without warning you have Shadow to thank. |

The Ascendancy of Plot

Emulating them encourages GMs to think in terms of "plot" and tempts them into railroading behavior. They can find themselves expecting a players to see plot revelation of their "living novel," the reward, and became less interested in offering the PCs rewards and satisfying challenges. (In fact, the whole 'milestone' advancement method seems to descend from this mindset. As is the habit of players wanting to being characters with elaborate backstory and motivations at the beginning of the story, rather than waiting to discover them.

The need for an epic, heroic saga fundamentally changes the focus of the game; rather than characters taking big risks to earn treasure, knowledge that was the core of the Dungeons & Dragons game loop, the game becomes a tale of heroism that focuses on derring-do. It changes the game from one about creative problem solving to one about combat.

The push to have GMs pre-create a complex plot that the characters ride rails to uncover created a schism in the way players perceive the purpose of role-playing games, and what the roles of GMs and PCs were in the world. I think this schism ultimately led to the creation of the Storygame genre on some levels. Dungeons & Dragons is not really meant to tell stories or have a plot: those things are emergent as players make choices and the dice fall. It is terrible at facilitating pre-designed plots. Making a new kind of game that does a better job of that is a natural, logical consequence.

Conclusion

Final Fantasy is a cultural institution globally. It was at first designed to emulate Dungeons & Dragons, and then took off to become a thing all its own. Now it has a far larger fanbase than TTRPGs ever could hope to have. But the fact that it was very much tied to its D&D roots until around the time Final Fantasy VII was released has meant that it has had a constant dialogue with D&D among the fans of both - which is a very large cohort of the second generation of Dungeons & Dragons players. Its fantasy settings and sophisticated characters did wonders for the richness of the fame when they were emulated.

On the other hand, some of the tropes used to subordinate the game to the Narrative are fundamentally at odds with good GMing. An attempt to emulate those parts of Final Fantasy have created some of the worst, most abusive conventions in table-top gaming culture.

The plots and Narrative of Final Fantasy, because they are rich and rewarding can be aspirational to a GM , but simply cannot be forced in a a role-playing game. The desire to be able to have more of that aspect of a living, visually engaging novel helped reshape the way D&D rewards its players, what motivates gameplay, and ultimately helped give rise to the Storygame genre.

The influence of the Final Fantasy games on the shape of Dungeons & Dragons and other fantasy TTRPGs and media are easily seen and felt today in the way the game is structured. the common bad habits of new GMs, and even how campaigns are designed. But the release of these games happened in a surprisingly short window of time just as the second generation of D&D players were developing their sense of style,.and looking about for inspiration. It might also be poignant to consider that they coincided with new editions of D&D (the Rules Cyclopedia, AD&D2e, the Black Box) that didn't include Appendix-N. The 90s D&D was not a gateway into the pulps the way its predecessors had been. Final Fantasy was perfectly timed to fill the void of role model for a campaign It is easy for players slightly older and younger to look at the cultural shift that occurred in gaming and wonder "what happened?" and "where did this trope come from?"

And many younger players looking at the modern, schizmatic nature of the hobby might not get how or why the divide between those who want story and those who just want to let the narrative emerge became so pronounced.

The role of Final Fantasy is an important but often missing piece of the hobby's history,

This is so on point.

ReplyDeleteIMHO the influence of video games on modern RPG's is completely underrated.

We are at the point where the derivatives of media influenced by D&D are now influencing the main game.

You can see this even in the current look of D&D from the more fantastical art, to play expectations shifting due to both mediums being labeled as RPG's, even though video games deliver a similar, but very different experience from RPG's.

IMHO this is largely behind the shift towards more 'story' based gaming we see D&D being marketed for.

This is a mistake. It will end similar to the way things did for white wolfs world of darkness line. A collapse in the playerbase.

Not that D&D will stop being the number 1 RPG - but when the inevitable downturn comes it will be much sharper than expected.

It really is so significant, but not much talked about.

DeleteIf you go back to 1990 with the DMGR-1 Campaign Sourcebook and Catacomb guide, which was the last official D&D product designed just to give DMing advice in the AD&D2e era, the advice was pretty clearly: 'Don't manipulate; your desires shouldn't dictate player actions. Let them explore where they wish.'

Then, suddenly we had this shift. A lot of people lay it at the feet of Tracy Hickman, as the Dragonlance D&D modules definitely had a very specific story to tell, and ran on rails between adventure sites. But it was really part of the zeitgeist. Video Games were a new medium and developers were desperate to prove they could 'tell a story' with them. Kids TV at the time was heavy on fate, prophecy, chosen ones, and coincidences, as well.

Its no wonder that the media that most felt like D&D like Final Fantasy and DragonQuest had a massive impact on how the kids of the time ran the game.

By 1998 unofficial advice you saw everywhere was more focused on how to write a good plot twist, what carrots to dangle in front of PCs, and how to avoid getting your campaign "Derailed".

Even the visual design in the 3rd edition was pretty clearly influenced by Yoshitaka Amano (Final Fantasy, Vampire Hunter D) and Ryo Mizuo (Record of Lodoss War, legend of Crystania) in design.

Definitely by the time you hit the Eberron art and Wayne A. Reynolds (who also did all the art for Pathfinder 1e) character designs were undeniably more influenced by Manga and Video Games than by Medieval European art and Western Comics.

And I definitely thing the "story" and "plot" orientation was pretty locked in by the time 3e was in full swing. In the official D&D forums people had stopped thinking of D&D as a VR simulation run on human hardware and started calling it a "living novel." which is a telling turn of phrase.

And now we have this new movement. The OC culture, where your D&D character is a sort of sacred expression of yourself that lets you express something in a performance-art-come-group-therapy version of D&D.

But it just isn't sustainable, because it doesn't lend itself to sustained, enjoyable play. The average game of D&D5e is 7 sessions, stays in the low levels, and most players don't play more than a single such campaign in a year. That is a very tedious-sounding mode of play.

In the meantime, D&D simply isn't serving its old player-base, except by selling reprints of old editions on DTRPG. We are small potatoes in the short term: we're outnumbered, and we won't spend $200-$300 on custom minis, art, dice towers, t-shirts, and totes every time we start a new campaign.

Once this style of play has run its course - and I do think that it is partially being extended by COVID Lockdowns, etc. - WotC is going to find themselves looking at empty conventions and rapidly declining sales. A lot of the current crowd are going to leave D&D and not come back to TTRPGs. Some more are going to go over to something like FATE Core or Numenera that does a better job of giving them what they want. Not as many as they think are going to stick with it.

And oldsters like me are going to be perfectly happy playing Low Fantasy Gaming, OSRIC, or Lamentations.

Agreed. People point at Hickman because he is an obvious example from the D&D side of the hobby.

ReplyDeleteBut Vampire the Masquerade also had its day in the sun! With its 'storyteller' system... Which heavily pushed the idea of the GM as a Storyteller. Metaplot also really reared its ugly head at this time with various supplements "advancing" the timeline of a setting to some 'compelling' conclusion. But it mostly showed that wanna-be authors should have just stuck to writing normal setting fluff...

But Vampire brought a lot of new people to the hobby, so RPG land was starting to get 'RPG's tell stories' from both sides in a big way.

And honestly RPG writers and game designers had been using the word 'story' as a vernacular short hand to imperfectly convey what RPG's do since the beginning of the hobby.

"What's an RPG?"

"Well it's like a virtual world where the GM runs everything but the player characters, and you create a character that..."

ZZZzzzzzzzz...

"You like Conan and lord of the rings? Well to get to run around and kick ass like Conan and Aragorn in your own story!"

"Cool! I can get behind that!"

And so the lazy and imperfect replaced the long winded and more precise...

Which has resulted in a lot of people in the hobby believing their own PR line thinking that the word 'story' means something that it doesn't.

The OC culture will result in a sharp decline when the bubble pops because these people do not reliably make the transition to good hobbyist GM's.

Every RPG is dependent on enough casual players liking the game that they make the move from a casual player to a GM hobbyist that will buy the product and run the game for future players.

IMHO "OC Culture" is just too shallow of a mode of play to hook casual players into becoming future GM's.

Especially since a GM's role is very different than that of a players, and it is a role fundamentally incompatible with what a lot of OC players want out of their RPG experience.

I believe that while not a abrupt as what they did with 4e, WotC is creating a situation where someone with some savvy can create a competitive product that will start to peel away market share when 5e really starts to decline.

It remains to be seen if someone will step up to the plate though...

I hadn't thought of the implications of OC culture on the DM supply. That is a great point. I am going to do some serious thinking on all of the implications.

Delete