I grew up in the province of Nova Scotia, and much of my family still lives out east in Nova Scotia or New Brunswick. Every year, I try to make my way back to spend time with my relatives, and to give my sons a chance to enjoy time with their grandparents.

Life there is slower and simpler. More humble than most of the hustle and bustle of the Western World. The people there, for the most part have deep roots in the land. They love family, music, home-cooked meals, time spent together. They like to be involved in small community societies together. If there are a people left in the world like Tolkein's shirefolk, it is Atlantic Canadians.

But, as much as visiting the people there can be a joy, travelling through the Maritimes fills me with Melancholy. It is a land that has been emptied out of its people.

|

| Cover Art to " Slumbering Ursine Dunes" by David Lewis Johnson. Adventure by Chris Kutalik ©2014, The Hydra Cooperative. I have been dying to get this book for ages... |

Amusingly, even the demographic data he presents shows the far untamed marches of Medieval Russia as more densely populated than Canada. But Canada is a wild land where almost all of the population is crammed within an hour's drive of the United States Border. It's when you journey through Quebec and the Maritime provinces that it really feels empty.

But the emptiness, the loneliness, and the decay of Atlantic Canada is truly heart-wrenching at times. I wanted to share this piece as a tool of sorts to World-Builders to give them snapshots and ideas of a place of Howling Emptiness in prose.

An Impression: The Slow Apocalypse

|

| My childhood home was just around the next inlet. |

The Apocalypse was still in process when I was a boy. Not storms, monsters or mayhem. It was death by Economics. The train we used to take from Halifax to Yarmouth shut down on the policy advice of the IMF. The closure of the stinking paper mills. Fish moratoria imposed to protect the cod... Not because we were over-fishing but because we were impotent to stop the hundreds of thousands of tonnes of fish stolen from our waters by foreign crews looking to dodge their own governments' restrictions.

More and more folks out of work.

It came at first with strange adaptations; the lady next to our school turned her house into a used book store. The lonely old man who used to fix nets by Todd's Island started making bird feeders for sale to tourists. The Masonic Hall advertising rental rates out front... Everyone could feel a cool wind. Even children who talked in fancy of ghosts and madmen and Nuclear War... We all knew the real monster was the house after house left empty by the roads with boarded windows.

When the Westray Mine collapsed in 1992, we all watched the disaster day and night praying for the men buried in the deep. Twenty Six dead. But when it was over, and the mine all gone, everyone still seemed to be holding their breath.

After that, began the exodus. No new mines, no new companies. Factories closing in the news every few months. The young people packed up one after another, heading West for work. Slowly the small towns emptied out. Then, the older people, whose jobs had held on, felt it, too. Smelters and mills closing, early retirement packages and moving help if they wanted it, to get them away from the dying countryside.

It is still happening, though it's pace is accelerating. I see Its results in a great loneliness everywhere.

Entering New Brunswick

The checkpoint at Madawaska is manned by police and forestry rangers. A weighing station converted into a tented stop in the time of the Plague.

Madawaska was once a stop at the end of a great emptiness. An Irving big Stop where people would refuel, eat greasy burgers, fill up on coffee and home-made pie after hours of winding mountain road closed in by Spruce Taiga. The houses nearby sold home-made souveniers, firewood, handicrafts, ice cream, and camping supplies.

They moved the highway a decade ago. Now, getting to the Big Stop is a hassle, the original Trans-Canada is a back-road accessible by a winding exit. The souvenir stand is boarded up. The campfire bins, empty. The house of the old couple who lived by the tourist trade is run-down. They cannot afford to paint it.

We hear the Mounties sigh about the car ahead of us. "He says he speaks French, but that's no kind of French I've ever heard."

We have our papers well in order. We can tell that it is a welcome surprise. One of the first all day. They don't really look at it. They ask the questions, they wave us through. They have bigger frustrations.

From here it is a long stretch of empty highway. A lumber mill and a Mik'maw casino are the only things other than the highway and forest we can see. On foot, this would be a day of hard hiking alone in the hills. My son wets himself long before we can find the next toilet after the Irving. We expected it.

Saint Quentin

Motorcycles and trucks spill out of the drive-through along a side road and onto the highway backing up traffic as they wait for a turn to grab coffee and doughnuts at the lonely Tim Horton's here. A final place to refuel before you journey across New Brunswick. A crossroads.

North, the Appalachian Range Route. Winding mountain roads, dotted with lonely houses all the way to Chaleur Bay. East: Highway 180, Le Road de Resources, a paved road made for mining camps and logging operations... not for casual traffic. There is no cell reception, no gas, not even houses. The police check for broken down cars about once every other day in the Summer; Gods help you in the Winter... most of the camps are empty now. There aren't even trucks every day. The asphalt disintegrates at the edges, crumbling into ragged jigsaw patterns.

The moose on that road are a peril, dozens of collisions a year. They say out East "If you hit a moose with your car, you wreck your car, and the moose is going to be pissed off."

People used to believe Le Road de Resources was faster. GPS and Google maps has proved that wrong. Now only fools and speed demons take it. The cops won't stop you from speeding back there... it's your neck. Both wind up in our destination.

The Appalacian Range Route

|

| Appalachian Range Route Marker Seen on the roadside in Quebec and New Brunswick |

The road itself is the business here. The hamlets do not have streets, they line up along the highway. Snow ploughers, postmasters, policemen, tow-truck operators, heavy machinery operators, and mechanics. The houses are a study in wealth and poverty. Some have elegant gazebos for hot tubs, and shining trucks; Others are unpainted, exposed insulation where storms have ripped the siding off. Old car seats bolted to the porch and wax paper over the windows. Abandoned houses slowly cave in by the road in numbers nearly matching the inhabited.

Class doesn't matter here; in a storm, they are all in it together.

The folks on the trail have to drive hours to get groceries. They buy supplies measured in months to keep in chest freezers. They all own their own generators. The winter can close them off for days at a time.

Campbellton

This place is heart-rendingly beautiful. Mountains of green shrouded in fog over a crystalline branch of the Chaleur Bay. Eagle nests on every other telephone pole. Half the houses by the highway are boarded up... The paint peeling. Parks full of kit homes made in haste to meet the needs of the mills, smelter, and docks, rotting away now, rows of identical empty homes.

The gas station we stop at is full of friendly people speaking the local French-English pidgin everyone jokingly calls Franglais. They smile and flirt with my children as we wait our turns for the tiny bathroom with the #gorgeous sticker on the antique mirror. The fridge here is full of home-made cookies baked by local women. The recipes are traditional ones to the region; I know exactly how they would taste. There is all manner of bric-a-brac from video game controllers to car parts, local artist's works to kites. It is one of the only places to buy and sell in town.

The bathroom has no changing station, I have to swap the baby's diaper in the parking lot.

Across the water we can see the hulk of the docks and smelter at Dalhousie. There hasn't been a ship in two years. And before that, the smelter handled silver from South American mines only once or twice a year. No iron or nickel from local mines has been smelted in years. It's rusted colossal chimney is already beginning to look abandoned.

Beresford and Bathurst

This is my wife's home town. The only place with more than a Wal-Mart and gas station for miles. The old pulp mill on the far side of the bay hasn't run in nearly 15 years. It is beginning to rust away. The people here used to work the mills, the mine, the smelter; they were paid well. Hot tubs, RVs, swimming pools and handsome homes were common. Now, there are "For Sale" signs everywhere as people try to claw back some of the money wasted on conspicuous consumption.

My In-laws are some of the last hold-outs of English-speakers in the region. The big companies saw political advantage to hiring a majority of Fracophone workers. Over the 21 years I have been coming here, I've watched English fade from signs and from the overheard conversation. The English-language highschool is shrinking little by little with its student body. The Anglo church yards are weedy, the tombstones poorly cared for.

The French here comes from three different ethnic groups. The accents are varied, and break along class lines. Quebecquois is an accent of wealth and influence. It's speakers came here for high-paying executive jobs. The Acadians with their archaic French are locals, often poor, but hard-working. The Franglais belongs to the French-Speaking Irish from "down shore." Its a mark of mild stigma, like a thick Georgia accent in New York City.

Here we spend two weeks quarantined with my in-laws so that we can legally move around the Maritimes for the rest of the Summer. People here are used to storms shutting the city down. Keeping two weeks of food for six people is child's play for my no-nonsense Newfie mother-in-law. Folks from The Rock are used to long winters spent indoors far from grocery stores. Card games with her are full of magic tricks, jokes and tall tales.

Even this spot, where most of the population of the county is seated is filled with shuttered businesse. The McMansions by the seaside are mostly for sale. The once brimming yacht club full of empty berths and run-down boats whose owners can no longer afford their upkeep.

Youghall beach is a beautiful strip of sand on a bay as warm as bathwater. It should be teeming with people trying to beat the heat. When our quarantine is over we are swift to head for the sand and the cool breeze. But people are scattered far apart. My son builds a kingdom of sand castles without going anywhere near other beachgoers. Geese nest on the beach unfettered for the first time since Man built a city here.

Miramichi

|

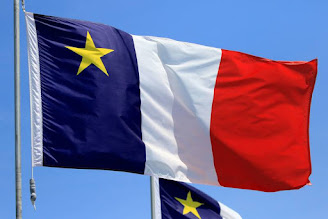

| Acadian Flags |

The sign says Miramichi is the Irish Capital of New Brunswick, and that might still be true, but this is also the heartland of my mother's people, the Acadians. You can learn much about prejudice here.

In 1755 the English took these lands entirely from the French. The settlers here were Acadians, a group of peasants that the French had considered to poor, ignorant, and too mixed with the Portugese and Spanish to be proper French. They had moved as many as they could out to the colonies, to give their land to more deserving groups.

Unwilling to leave a potential enemy at their back, the English called the men of every Acadian community to the Church at Grand Pré, promising to come to peaceable terms for their subjugation. Once they had enough men present the English held them at gunpoint, and marched them onto ships. Over the next few days, they hunted down as many Acadians as they could, rounded them up and put them on vessels. With no eye to keeping families together, they carried them to France, Georgia, Louisiana, and the Caribbean and dumped them on French-Speaking shores.

With no way to find out who was where, the Acadians came back on foot or by barge over a couple of decade. Unwelcome in English land, they hid, often helped by the Irish and Dutch who had been given the Acadians' land. They established backwater villages out of sight and out of mind here and along the NB coast. Many were dotted along the Miramichi river.

The lesson I learned visiting Miramichi as a half-Acadian teen is that if you have no one around that looks different, people will find a next best reason to be bigoted. Acadians were called by Canadian scholars as recently as the 80s "The White Niggers of the Miramichi." And they sure as hell got the treatment.

My great-grandmother didn't want that for her children. She chose to teach them English and speak it at home. She didn't think there was a future for Acadie. She became protestant just to be able to go to an English church near her Cape Breton home. Nobody taught me what Acadians were supposedly like until I crashed straight into the bitter splits in the community here.

But, the Acadians work hard and have thick skins. They work hard and worked cheaply. For awhile the mills and factories sprung up around them. Now the river is lined with rusted hulks of machinery slowly bowing into the water. The suspension bridge here is rusty and decaying. People are afraid to cross it, but the province can't afford to bypass it. There is always work being done to keep the bridge from falling into the river.

There are few starker reminders that there are no longer enough people here to create the wealth need to keep the province afloat.

Highway 11

The highway between Miramichi and Moncton is old and worn down. Two narrow lanes crowded with trees. Almost a decade ago, the province started a project to twin the highway, but the budget could barely support it. A change of government left long swaths of bulldozed land and half-finished bridges to sit untouched for years. We are surprised to see bulldozers and work crews back to work on it after years of being abandoned.

Sackville

Sackville sits on the Northern edge of the Tantramar Marsh, hundreds of kilometers of saltwater marshes and moors, thick with shallow rivers.

The Apocalypse started here. Before 1911, Sackville hosted a massive shipyard. Timber and steel from around the province would come here where massive merchant vessels would be built in the shallows, then brought through a canal into the Bay of Fundy and then on to the Atlantic. For the young men of the town, it was a rite of passage to sign up with the Merchant Navy and travel to the far East, bringing exotic mementos home before settling down to work the yard. The old homes and antique stores here are filled with lanterns, fans, vases, screens, and robes brought back from China and Japan. The architecture of the Far East accents the oldest homes.

In 1911, an earthquake collapsed the canal. Mud and marshwater refused to be held back for the repairs. In the end, it was cheaper to move the shipbuilding to Amherst at the far end of the marsh than to rebuild.

|

| Mt. A's Swan Pond and Convocation Hall, Seen from the music conservatory garden. |

All that is left to support the town is the University. My family has gone here since it was a Methodist girl's school in the 1880s. Our roots here run deep. My grandparents met and fell in love here. My wife and I did, too. I can see the walkway through the waterfowl park where I got down on one knee in the snow and proposed to her, from the highway.

But it is the Summer, and Sackville is empty this time of year. Students are 2/3 of the town's population. Businesses often close. And most of our old haunts have closed down or changed hands. Nothing stays the same here. The town changes to suit the fashions of the young.

The only reason to stop here is the highway exit. McDonald's, Tim Horton's a gas station, the farmer's co-op and the booming cannabis store. This time of year, it is just people passing on through.

Entering Nova Scotia

As you cross the Marsh, the old CBC AM broadcasting station draws your eye with its emptiness. This was once the site of the world's most powerful broadcast antenna array. It could make the CBC heard on the other side of the planet. As a child, that web of wire and steel towers was a landmark. Now it is an empty, level spot. The antenna was dismantled and sold to foreign buyers.

The checkpoint here is close to a colossal wind farm. The turbines stretch across the marsh, impossibly huge and impossibly far. They are weirdly new-Looking in a landscape of old, worn buildings.

The checkpoint is manned by rangers; we don't have the police force here to do the job here. They are puzzled, but not surprised by our paperwork; we filled put the forms the website said to, but they are the wrong ones. Nothing is explained well; they are used to it. We are told to call Telehealth Nova Scotia and explain, with our entry number, that we were already quarantined in New Brunswick, and get verification that we need not do so again.

The highway here is dedicated in memory of the Westray Miners. Normally these dedications change every few years, but not this one. A part of the province died with those 26 men.

When we finally get through to Telehealth five hours later, they have no idea why we were told to call them. But they make a note and tell us to enjoy our visit.

Oxford

The nearest town to my parents' home, the Apocalypse is fresh here. Last year, the local community hall and swimming park were shut down as a massive sinkhole opened up. Natural erosion of basalt under the town.

At first the gas station across the street closed, too. And students at the nearby school had to be bussed to Pugwash, 25km away. The scool there was too small. Oxford's teens and teachers were on the night shift.

The hole has been surveyed now; the students have returned to school, but the park and community hall are derelict. The sink hole cannot be filled with The county's budget. And the time it took to learn that and let businesses reopen has caused the one restaurant and one of the two hotels in town to close permanently.

Oxford's livelihood is blueberries. A processing plant washes, packages, stews, preserves, and tins blueberries in many different ways. It is, for now, one of the three big employers left in Cumberland County. The salt mine in Pugwash and the logging operation towards Springhill are the other two. There have been a few bad seasons lately; the locals worry about the plant. Their town is shrinking before their eyes; swallowed up by the Earth and there is not enough in the coffers to do anything but watch it go.

Beyond the short strip of stores I carry on to my parents' home. Here we are in true wilderness; like the Appalachian Range Range, every home has a generator, a rifle, and a deep chest freezer to hold supplies to last the Winter in case you cannot get fresh food from town. Many keep tractors or excavators on hand to care for their land.

On lazy days, I watch the River Philip. The salmon come down the River and rest among the gravel bars where the water is brackish, so they can acclimate slowly to different salt levels before transitioning to fresh water from the sea, or from sea water to fresh. Bald Eagles and Osprey come here in families; birds so big they seem to take up the sky. The Great Blue Heron, Merganzer Ducks, Kingfishers, Night Hawks... The sky is full of them. White-tailed deer, black bears and coyote are easily seen in the meadow across the water. There are not enough people here for them to be afraid.

It can be hard to sleep in. Logging trucks and dump trucks loaded with salt rumble down the road. I am up every day with the sun as it paints the sky fuscia.

Cumberland County

Kolbec road takes us along a winding path to the coast. Farmhouses turned silver collapse in tombs of poplar trees. There are so many lonely, abandoned houses here. And graveyards enough that the dead outnumber the living.

We take to the sea to Heather Beach with its hot red sand and warm water. Ramshackle summer cottages crowd as close as they can to the water. Spice racks and bookshelves full of suntan lotion wait on sheltered stoups so children may run out to the sea as soon as their breakfasts have been eaten. It us a place for boardgames and second-hand novels. Long days unplugged

We go to my grandmother's funeral in a fishing village where the docks are still lined with lobster pots, and fishing boats older than I still go put in the mornings. She died in January, but we waited for August to say goodbye so as many of us could come as possible. We all agree that It was best that she passed on before the plague would habe left her alone and confused in her nursing home, with no one to visit her and bring her back down to Earth. We love one another deeply, and take pleasure in seeing family so close again.

Joggins

We take my son to the Fossil Cliffs at Joggins one morning. To let him see trees hundreds of millions of years old in solid stone embedded in the cliffs. We collect petrified insects, plants, and mollusks to examine. Life that passed away long before the dinosaurs. It was fossils from here displayed during the great debate between Huxley and Wilbeforce that established that Science and Reason must supercede Religion in the public sphere. These stones re-wrote the priorities of the Western World.

We pile our fossils neatly on a petrified tree for the next visitor to enjoy, and eat ice cream on a park bench before driving home. Humbled by the experience. But with all of the empty buildings around us, we can't help but feel like we are living fossils, ourselves.

With no easy way to recycle scrap here, many houses decorate their yards with brightly painted sculptures made of old bicycles and car parts. It is a strange, cheerful sight.

I read the road signs for my oldest son on the way back to Oxford, as they never got around tonreplacing them with modern ones that use pictographs. Most are 50-60 years old.

Homeward

I am not glad to turn homeward to Ontario. The joy of family, the roar of the Ocean, and the Celtic melancholy of this place feed my creative soul. I meditate, pray, and write poetry when I am here. The hustle and bustle of the cities of Ontario separate me from my soul, and find me moving to the ticking of the clock. But the place has become so empty, so lonely, that it feels sometimes like after I leave, it will all finslly disappear. Emptied and left to turn silver like an abandoned farmhouse.

Great post and beautifully written. Thanks for sharing the details of your trip.

ReplyDeleteThank you! In a way, I just wanted to make sure the places and people were thought of and remembered. In another, I wanted to see if I could bottle that melancholy and turn it into a tool for others.

Delete