|

| Photo by Djedj from Pixabay |

When designing adventures, many GM's make it a point to try and give every character a chance to shine. This is a great practice in theory, and givrs players an opportunity to really play their characters to th hilt. In practice, however, it often boils down to making sure that there's some undead to turn for a cleric, a bunch of mooks for the fighters to demolish, and a trap to disarm.

There is a fundamental flaw in the way that this idea is often executed or described to new DMs, The reflect the mechanics of a character class, but they don't reflect the character. Do that, you have to establish why they're playing the character that they are.

Hopefully, that is not in the name of "party balance." Player should never have to feel like they must play a character they don't enjoy to fill a checkbox.

Of course, if you are building your characters as Crom intended, and rolling 3d6 down the line, then, the players are playing the characters that the dice gave them, and hopefully enjoying the experience. At which point, the question becomes what is most enjoyable about the character they have.

A good starting point if you are playing with randomly generated characters, are writing to publish, is to look at the literary archetypes on which characters are built. Each class in D&D is built to enable a player to emulate a range of heroes from the body of literature that inspired the game: Appendix N.

The same is true of every other class-based RPG: they are built to emulate either genres of literature (been I include cinema, comics, video games, and television) or specific works. Each genre has its set of archetypes and stock characters. The classes are a way of distilling the abilities of that archetype down into something gamable.

But the trick here is to remember that the map is not the territory. A class lets a character do the sort of actions that the archetypal character often does in the process of their heroics, but that is not the same what those heroics are.

|

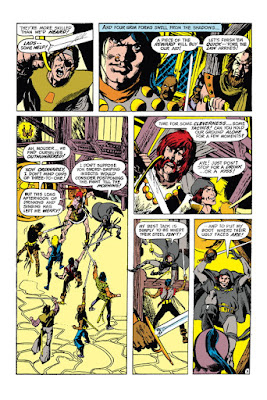

From "Fritz Leiber's Fahfrd and Grey Mouser: the Cloud of Hate and Other Stories"; ©2016 Dark Horse Comics |

Let's take the Grey Mouser as an example. Mouse was one of the templates for the Thief class in Dungeons & Dragons. He picks locks and pockets, he is nimble and dodges attacks rather than wears much armour. He dabbles a bit in magic, but never mastered it. But those are just a few things he does. What he is, is a clever little man who uses speed and wit to outbox foes far more powerful and deadly than he is. Mouse out-thieves the Thieves Guild and even evil gods.

Giving players a chance to have a really satisfying encounter involved tailoring the encounter to the Archetype not the game engine.

If you can tailor an encounter to meet the fictional characters that inspired the class, then players will feel like they have served real purpose and feel more immersed in their character.

I am going to break down the Archetypal play goals for the four definitive OD&D classes.

Fighters and Other Warriors

|

| Image by ArtTower from Pixabay |

If you approach designing an adventure by looking at the mechanics of the character class, the obvious thing to do with the fighters make sure there's at least one combat encounter. if you do it this way, you might luck into a satisfying encounter for a fighter.

If, on the other hand, you look at this from the archetype of warriors in Appendix N fiction, you'll see that there are two things that a weird fiction heroic warrior does very well.

The first is swashbuckling: combining your martial skill with your wits and the environment to create exciting moves that disable an enemy without having to plug away at their hit points. Dropping chandeliers on foes, pulling down tapestries, hacking a part bridge ropes, swatting weapons out of an enemy's hand, catching a thrown weapon in hurling it back... all of these are excellent examples of how a warrior performs heroics in sword & sorcery narratives. Or any good action story, for that matter.

The other thing they do well is incredible displays of fortitude and willpower. They shrug off enchantments, scare enemies into surrendering with a look, resist torture, stand that extra minute to let others escape, smashdown barricades and bend steel bars.

If we, as DMs want our PCs to feel like a mighty warrior from Appendix N literature, we have to encourage that kind of action. We do this by setting up an environment where I where your might have greater effect by using the environment than swinging sword. And we create obstacles that are most easily overcome by smashing.

Since I started playing Dungeon Crawl Classics RPG, I have made it a point to import some form of the Mighty Deeds of Arms mechanic, because it encourages players to try something special every time they make an attack roll.

In an upcoming dungeon design project I will be sharing here, I have a door that needs kicking down for the quickest way to rescue the prisoners in the cells. I have chains that can be sundered to free prisoners more quickly. I have an enemy who is there to hinder the players from saving lives, who can be challenged a duel, while the other PC set about freeing prisoners. And I have a sophisticated battle on the gantries above the dangerous machines, which will reward clever swashbuckling maneuvers such as lassoing enemies and yanking them to their Doom.

Clerics and Paladins

|

| Image by OpenClipart-Vectors fr. Pixabay |

In the earliest editions of Dungeons & Dragons, Clerics were supposed to fill the role of oracles, miracle workers, monks, evil cultists, saints, holy knights, chosen heroes, and witch hunters. That is why they didn't even get magic until second level: they were meant to be heroes first, and a magician second. Even the low-level clerical magic looked more like a lucky break a boost in morale, or a surge of Faith, rather than a flashing miracle. low-level clerics are meant to look more like Solomon Kane.

Giving them flashier magic, making their magic available at first level, and separating out the Paladin role to a separate class muddied the waters on clerics quite a bit.

At the end of the day, what a cleric is, is a chosen warrior or a wise mystic. Making sure a player gets to feeling that that is what their character is becomes critical to making sure that clerics are enjoyable to play. And, if there ever was a class that needed special attention in this department, it is the cleric

Making the chosen warrior archetype work is a matter of making sure that the character is given temptation to refuse, or an enemy so demonic and terrible that standing against them is heroic to a fault.

This is why we have irredeemably evil humanoids in Dungeons & Dragons. The undead don't make choices. Bestial monsters like owlbears just do what they do. It is the evil cultists, or the willing participant in a culture of rape torture and cannibalism that makes a cleric not just a tomb raider, and not just a bystander, but someone who actively chooses to do good when it is terrifying and dangerous to do so.

In the case of my upcoming adventure, the PCs are up against slave taking monsters out of time that butcher live animals cruelly, throw their slaves away into garbage pits to die, and threaten to eat or enslave the population. Setting their captives free, defying their leaders, and destroying their cruel machines will definitely make a cleric seem like an incorruptible hero.

The wise mystic is actually a lot easier to work with. These are characters who're in the adventure because they are destined to be there. A Higher Force drives these characters. If they running the goblins, it is because the gods do not want those goblins to harm the innocent. If they are seeking out a treasure hoard, is because that coin can go to the service of a greater good or some magical treasure within can be turned to holy service.

The best way to make a wise mystic character feel special is to make sure that the adventure itself is exceptional. Having characters be the ones to discover an ancient evil and prevent it from rising will appeal to the mystic player. When in doubt, it is useful to have a vision, or a rumour drop it to the characters locks that connects to a church, a holy order, or a natural disaster.

Thieves

Whether you call them thieves, dress them up as rogues, or give them another name, the point of this character is to be a clever scoundrel. An Indiana Jones a Gray !ouser, for a Prince Corwin.

The Thief's player doesn't just want disarm traps or pick locks. Those are a means to an end. What they want is to be smarter then the opposition. They want to be 5 steps ahead, use a clever trick, outwit, or run circles arounf their enemies.

This is why players controlling thieves are the most likely to turn on other player characters. If they are simply used get past the mechanisms of the dungeon and not to steal treasure right out from under a dragon, confuse a monster with a word game, or panic a guard with a well set fire or tossed scorpion, they will not be actually playing the character they imagined they would play.

Check out this video from Dungeon Craft on playing thieves for more:

in this adventure, I made sure that roguish characters can actually save the day by picking a lock on a slave's chains. Are the most likely to succeed in disarming a ticking time bomb, and, if they can out-think the sentries they can choose to work around a dangerous encounter and can prevent the party from being at a disadvantage in the two large fight sequences.

I am also making sure that some of the treasure in here, like to sleep poison munitions, enables thief even character to do more of what they do best.

The Magic-User

The magic user is often played as a blaster, or a battlefield control specialist. Certainly they excel at these roles in any of the more tactical recent editions of Dungeons & Dragons. It is not what they were built to do in older versions of D&D, and not what the archetype that inspired them does.

iI you are playing an edition of Dungeons & Dragons that treats wizards as a controller, and that is clearly what the player is aiming for, all you need is a technically complex encounter with the number of weak enemies.. I would expect, however, that this can become almost as unsatisfying as a thief who only ever disarms traps and never tricks anyone.

The real reason a lot of people want to play magic-users, is because they can break the rules. A wizard can reject the reality you put before of the players and substitute it for one that favours the party.

In old school games, the magic-user didn't get many spells, because every spell was a complete game changer. Sleep could knock how huge numbers of foes; Light didn't just replace a missing torch when was most needed, it could be weaponized to blind enemies. Unseen Servant created a henchman that could he sacrificed without any guilt to trigger traps or scout ahead.

Even the lowly magic missile was a guaranteed hit that bypassed protection from non-magical weapons and well it did little damage, monsters had far fewer hit points.

In order to give a magic-user player a chance to play the role of the reality-changer and game breaker, you need to put complex situations in front of the player characters where low-level spells could make a huge difference.

It helps to remember that the problems you put in front of players need not have clear predetermined solutions. Forcing the players to overcome a problem with no clear answer is when the magic-user really shines. It engages the creative itch that these characters are meant to scratch.

No comments:

Post a Comment